Day the Third: I'm running through my ten most influential albums, thanks to the recommendation by my high school buddy, Matthew Wilhite. I'll continue my trek with an album that really demonstrates a lot about what "high school JD" was all about--and what that guy would turn into in the years to come.

Autumn 1986. Sophomore year. Like most other 80s children with little taste, I had felt my heart leap to Air Supply; I thought Phil Collins was cool; I liked Weird Al Yankovic. In other words, I had little taste of my own.

Autumn 1986 was also the season in which I took my final piano lesson. My valediction at my final recital was the first two movements of Beethoven's "Sonata Pathetique." I was and will always be proud of that accomplishment. I was beginning to play by ear, and my keyboarding future could have gone anywhere.

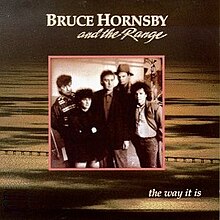

Into this period of my life, ripe for change, burst Bruce Hornsby and the Range and their classic debut album, "The Way It Is." The album, arising in the gap between Michael Jackson's two biggest albums (Thriller and Bad) and just before the rise of Whitney Houston, held such a different sound, it took radio by storm that winter and brought Hornsby a best new artist Grammy in 1987.

I was drawn to Hornsby--as I was to Elton John--because he was a pianist who also sang. I had taken piano lessons most of my life; I loved singing. These artists combined the two skills, and they looked and sounded really cool doing it. I bought sheet music for the album, trying to learn Hornsby's notes. It was too hard. I realized that I'd never match the notes, I would have to match the style.

So I looked above the notes on the sheet music for the chords, and I followed them, learning to branch out and add twists of my own. I loved Hornsby's use of drone notes (playing the same low note on phrases that riffed on the same chord), and I figured out how to take a basic chord pattern and riff or jam with it until it was something uniquely my own. Hornsby wasn't a ticket into country-style rock, but beyond that into jazz and, eventually, bluegrass.

While Hornsby's style carried the day, the album had a huge influence on me beyond the keyboard. The title cut, with its outrage over Reagan-era indifference to injustice, confronted my conservatism at the time (I was a huge Reagan-Bush guy before I studied outside the United States and got a little more perspective).

In a time when little kisses first became a huge part of my life, "Every Little Kiss" captured my feelings, while "Down the Road Tonight" hinted at sin and the kind of things that weren't discussed at a Christian high school.

But my favorite songs were the lyrical landscapes of lesser tracks like "River Runs Low," "On the Western Skyline," and "The Red Plains." I was reading novels on my own (they weren't assigned in my high school), and I was really deep into John Steinbeck, whose books evoked the landscape of the Dust Bowl (Grapes of Wrath) and northern California (Of Mice and Men, The Pastures of Heaven).

My mind was filling with exotic landscapes beyond the hills of southern Ohio or middle Tennessee, and my fingers were creating exotic new soundscapes on the keyboard post-Pathetique.

A few years later a "western skyline" would welcome me and Jenny as we drove through Black Jack Canyon from New Mexico into our first Arizona sunset, a "mandolin rain" would accompany my own strumming on the instrument, and I would seek to change "the way it is" as a teacher leader and educator in public schools.

"The Way It Is," looking back, is The Way It Would Be for me in so many unique ways that I could have never foretold in autumn 1986. I guess that makes it a pretty influential album!